he security of physical assets depends not only on access control policies, but also on the mechanical integrity of the locking systems themselves. As intrusion techniques continue to evolve, one method that has gained attention is lock snapping—a mechanical attack that exploits structural weaknesses in certain cylinder-based door locks. Because it can be executed rapidly and with minimal noise, lock snapping presents a significant vulnerability in residential, commercial, and light-industrial environments.

This article is intended as a technical reference rather than a general overview. It focuses on how lock snapping occurs, how to evaluate locking systems for susceptibility, and how to specify appropriate countermeasures based on application risk level. The discussion is grounded in practical engineering considerations, including material strength, load paths, mounting geometry, and failure modes under forced entry conditions.

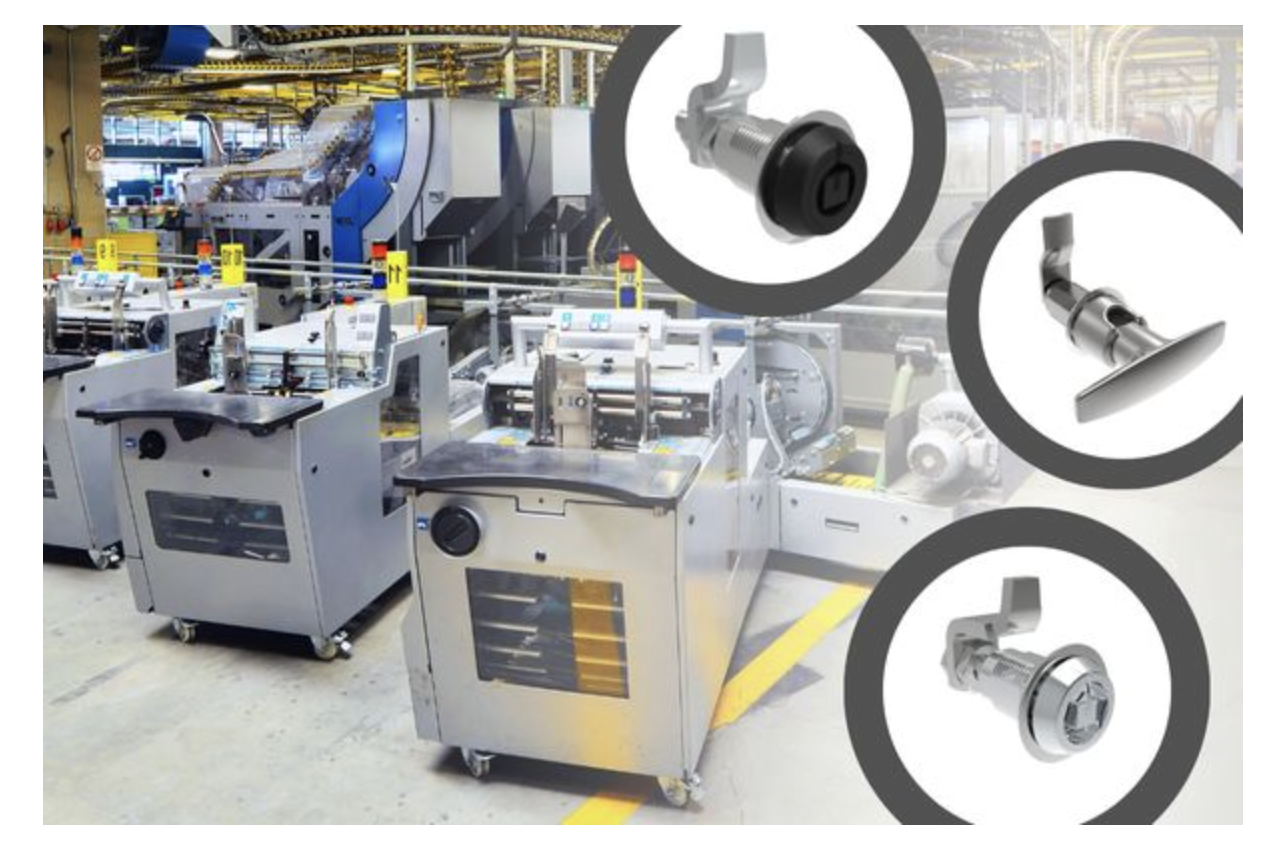

Drawing on experience from real-world industrial applications, Baotai works closely with OEMs, system integrators, and facility operators to address security challenges in demanding environments. These include machinery enclosures, access panels, electrical cabinets, and perimeter doors where both security and operational reliability are critical.

This article provides a structured evaluation checklist covering multiple use cases—from architectural access points to heavy industrial equipment. By understanding attack mechanisms and matching them with correctly engineered locking solutions, engineers and decision-makers can reduce vulnerability, improve system robustness, and select locks that deliver long-term protection under real operating conditions.

What Is Lock Snapping?

Lock snapping is a mechanical forced-entry technique that targets a specific type of lock cylinder—most commonly the Euro profile cylinder, which is widely used in residential, commercial, and light-industrial door systems. The cylinder is the critical component that houses the keyway and directly actuates the locking mechanism.

The attack exploits a structural weakness inherent in standard Euro cylinders. Because part of the cylinder typically protrudes beyond the door handle or escutcheon, an intruder can apply external force using simple hand tools such as pliers or a wrench. By gripping the exposed section and applying bending or torsional force, the attacker fractures the cylinder at its central fixing point—its weakest mechanical cross-section.

Once the cylinder is snapped, internal components such as the cam and locking interface become exposed or disengaged. At this stage, the remaining mechanism can be easily manipulated, allowing the door to be unlocked without the original key. Under real-world conditions, the entire process can be completed in a matter of seconds and with minimal noise.

From an engineering perspective, lock snapping highlights the importance of material strength, fracture resistance, controlled break points, and protective hardware integration. At Baotai, these failure modes are key considerations when developing locking solutions intended for higher-risk or industrial applications, where resistance to mechanical attack and long-term reliability are essential.

How to Identify a Vulnerable Lock

From a mechanical security standpoint, the primary risk factor for lock snapping is excessive cylinder protrusion beyond the door handle or protective escutcheon. Any exposed section of the lock cylinder provides a leverage point that can be exploited during a forced-entry attack.

You can assess vulnerability using the following on-site inspection procedure:

-

Inspect the door handle and locking assembly from the exterior side.

-

Identify the lock cylinder at the key insertion point.

-

Measure how far the cylinder protrudes beyond the surface of the handle or escutcheon.

-

If the protrusion exceeds 3 millimeters (approximately the thickness of two stacked coins), the lock is considered high risk.

From an engineering perspective, the exposed portion of the cylinder functions as a lever arm. When an attacker applies force using hand tools such as pliers or wrenches, this leverage concentrates stress at the cylinder’s weakest structural point—typically the central fixing screw hole. Once the stress exceeds the material’s fracture limit, the cylinder snaps, allowing direct manipulation of the locking mechanism.

How to Prevent Lock Snapping

Lock snapping vulnerabilities can be effectively mitigated through proper component selection and installation. The following countermeasures address both mechanical failure modes and attack vectors.

1. Upgrade to an Anti-Snap Lock Cylinder

Standard cylinders can be replaced with anti-snap lock cylinders specifically engineered to resist fracture-based attacks.

These cylinders typically incorporate two critical design features:

-

Sacrificial snap line

A controlled weak point is engineered into the external portion of the cylinder. If excessive force is applied, only the exposed tip breaks away, while the internal core remains intact and continues to secure the door. -

Reinforced internal structure

A hardened steel bar or pin runs through the cylinder body, significantly increasing resistance to bending and torsional forces. This reinforcement prevents the cylinder from fracturing at the central fixing point, even under sustained mechanical attack.

When specifying an anti-snap cylinder, engineers and specifiers should verify compliance with recognized security standards and test certifications.

At Baotai, resistance to fracture, controlled failure behavior, and long-term mechanical stability are key design considerations in locking solutions developed for high-risk and industrial environments.

2. Ensure Correct Cylinder Sizing

Even the most advanced anti-snap cylinder will underperform if incorrectly sized.

Best practice:

The lock cylinder should protrude no more than 3 millimeters beyond the handle or escutcheon. Ideally, it should sit flush or slightly recessed.

Excessive protrusion reintroduces a leverage point, allowing attackers to apply force regardless of internal reinforcements.

Before specifying or replacing a cylinder, accurate measurement is essential:

-

Measure from the central fixing screw hole to the outer face of the handle or escutcheon

-

Take measurements for both the interior and exterior sides

-

Select a cylinder length that minimizes exposure while maintaining functional clearance

3. Install a High-Security Handle or Protective Escutcheon

For applications requiring enhanced protection, upgrading the door hardware itself provides an additional defensive layer.

High-security handles or escutcheons incorporate a hardened metal reinforcement plate that fully surrounds the lock cylinder. This design serves as a physical shield, preventing direct tool access to the cylinder body.

By eliminating exposed gripping surfaces, the protective hardware effectively neutralizes the lock-snapping attack vector. When combined with an anti-snap cylinder, this configuration provides one of the most robust mechanical defenses available for door security.

Engineering Summary

Effective protection against lock snapping requires addressing three key factors:

-

Cylinder strength and controlled failure behavior

-

Proper installation and minimal protrusion

-

Physical shielding to eliminate leverage points

By applying these principles, and selecting locking solutions engineered for real-world attack conditions, both residential and industrial facilities can significantly reduce forced-entry risk.

How to Choose the Right Locks for Different Scenarios

Protecting a front door is important—but in industrial environments, security requirements extend far beyond basic access control. Industrial assets are higher in value, exposed to harsher conditions, and often located in unattended or remote areas. In these cases, a conventional lock is rarely sufficient.

As a lock manufacturer, Baotai has worked with customers to secure everything from compact enclosures to large-scale industrial machinery. Based on this experience, the key to effective security is selecting locking solutions that match the environment, risk level, and operational requirements of each application.

Below, we examine a common industrial scenario and the most appropriate locking solution for the job.

Securing Outdoor Infrastructure

Consider a roadside 5G telecom cabinet, a traffic control enclosure, or an electrical distribution box installed in an open field. These installations are typically unattended, continuously exposed to environmental stress, and house critical equipment.

Such applications face multiple threats simultaneously:

-

Rain, snow, dust, and temperature fluctuations

-

Corrosion caused by humidity or pollutants

-

Unauthorized access, vandalism, or forced entry

In discussions with telecom and infrastructure operators, the most common concerns are water ingress and physical tampering. In these environments, a lock failure often leads directly to equipment damage, service interruption, and costly repairs.

For this type of application, Baotai recommends quarter-turn latch solutions designed specifically for outdoor and industrial use. As you can see from: https://www.btlatch.com/product-category/locks-latches/cam-latches/

Recommended Solution: Baotai Quarter-Turn Latches

Baotai quarter-turn latches are engineered to meet IP65 protection requirements, ensuring:

-

Complete protection against dust ingress

-

Resistance to water jets from any direction

To ensure long-term reliability, these latches are manufactured from stainless steel or high-strength zinc alloy, providing excellent corrosion resistance and mechanical durability. This makes them well suited to harsh outdoor environments where standard hardware would quickly degrade.

In addition to durability, the quarter-turn operating mechanism allows:

-

Fast and intuitive access for authorized maintenance personnel

-

Reduced service time during inspections or emergency repairs

-

Secure closure with minimal operating force

By combining environmental sealing, mechanical strength, and operational efficiency, Baotai quarter-turn latches provide a balanced solution for protecting outdoor infrastructure against both environmental damage and unauthorized access.